When He Ruled The World: The Kurtis Blow Interview

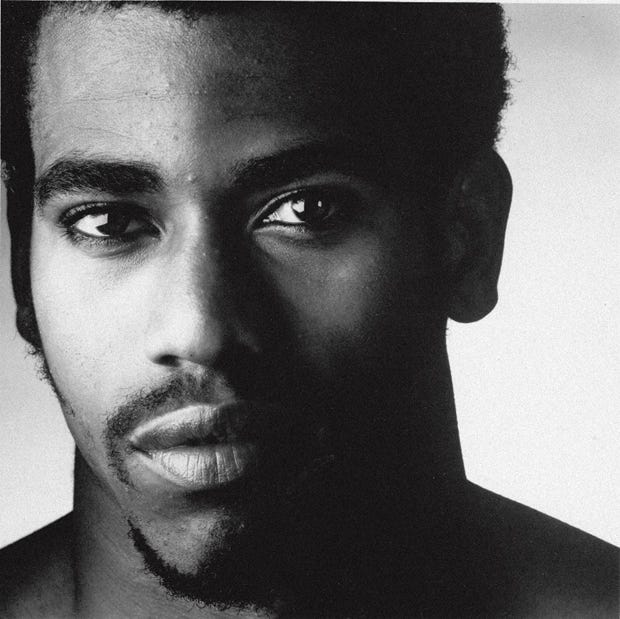

Kurtis Blow. Press photo courtesy the Adler Archives.

Originally published for Wax Poetics.

By 1989, De La Soul had just debuted 3 Feet High & Rising. Biz Markie released his first post–Marley Marl project, The Biz Never Sleeps. And the Beastie Boys came with their stunning sophomore effort, Paul’s Boutique.

To put things in perspective, Kurtis Blow was by now on his ninth studio album, had toured the world, and had been a megastar for ten years. He also produced a string of hit records throughout the ’80s and was in many ways the face of hip-hop in the mainstream (and international) arena. As the decade closed, he’d reached a comfort point in his career, a career of huge albums, top singles, and game-changing benchmarks. If cool Kool Herc was hip-hop’s Big Bang, Kurtis was Neil Armstrong, a man of firsts, breaking barriers with each step.

Here was a Harlem kid who in 1983 was performing in front of thousands at the Tokyo Dome in Japan. In addition to landmark concerts, his booming voice inadvertently made him rap’s first ambassador. Kurtis recalls: “When I was in college, I was a communications major. I studied orators and the processes of speech and how to project your voice. I always broke down rapping versus speaking and so forth. But to be tossed in the position I was in, to be a spokesman for rap all over the world, that was truly something else.”

Though rappers would often later be criticized, earlier rap had already found a perfect, Jheri-curled poster boy in Kurtis. Squeaky clean and well spoken, driven and young, he adored the spotlight as much as it adored him. And while there were notable contemporaries — Melle Mel, Lovebug Starski, or DJ Hollywood, for example — all lacked the charisma that made Kurtis a commercial king.

Minus a thuggish outing on “8 Million Stories” (featuring Run-DMC, who, succeeded Kurtis as rap’s mainstream face), Blow was perpetually positive, overtly G-rated, almost to a fault. It’s interesting to note that before he blew up, Kurtis ran with street gangs and even overcame a dark stint with drugs and alcohol. But all that was nothing to dwell on, as he explained: “Once I made it big, I wanted to celebrate the positives in life, not backtrack to how life was like in Harlem. My neighborhood was just all very happy for me. Why would I continue on being negative and just talk about bad things? It was about uplifting, you know?”

Kurtis stuck to his hustle and deepened his faith, releasing almost an album per year through the early ’80s. He was among the first to appear in film soundtracks and to star in Sprite commercials; he was the first rapper ever to hold a gold record. A legit 9-minute duet with Bob Dylan (called “Street Rock” where Bob “raps”) exists.

These days, Kurtis “Blow” Walker is a minister, serving similar uplifting messages in sermon form. In the early 2000s, he even had releases that proclaimed his faith and fondness for the church. Though platforms have changed, the sum of his life’s work led him back to what he always was — a public speaker, a communicator. Here’s a conversation with Kurtis on his remarkable rise to stardom and the wonderful times, people, and events that shaped it.

You were rap’s first major celebrity. How did that affect you being as young as you were? Had you always wanted to perform?

Personally, it was very rewarding in the beginning, especially ’79 to ’85. Best times of my life — traveling, meeting all different people around the world. I was the first rapper signed to a major label, meaning that they had offices in every major city in the world. First rapper on a major label. So every time I made a record, they’d fly me out to these offices in Paris, Belgium, Berlin, and so forth. It was amazing.

Were you slated to play or did they actively want you to represent rap?

Sometimes, it was for a tour, but sometimes they’d just send me places. And when I got there, they would have all kinds of press set up — from radio, to print, to television; one interview after the next. It was fun though. I was the first person in hip-hop to have to go through all that. Everybody at the time was so curious about this thing called hip-hop. I was literally trailblazing the path for rap, and I was just barely twenty years old. I remember because I found out while I was in Europe that my record hit number one! And I was no older than twenty-one at the time.

What was the international response to hip-hop then? Was it exoticized or was everyone just really curious?

Oh man, everyone was just so interested. [laughs] Like, where did this hip-hop come from? How come you guys are break dancing? Where’s your band? What does a DJ do? It just worked out to where it was a real interest story, because it came straight from the ghetto.

Were you overwhelmed or had you always wanted to perform onstage?

It was always a dream of mine to be onstage and become a singer or musician. I went to college and my major was communication, so I knew I’d do journalism or broadcasting or something related to those fields.

Before picking up the mic, you started out break dancing?

Yeah, [laughs] I was thirteen years old. Actually, I was a DJ first, because I was the family DJ. I was eight years old and remember being infatuated with record players and all the components that made it work. I would sit and stare and watch the mechanics of it all. My mom knew this, so I became the designated DJ at family functions, Christmas parties, and all that. I used to run around with my pen and pad and get requests from everybody and then run and play ’em. [laughs]

What made you switch to vocals?

I started checking out all these DJs when I was really getting into hip-hop. I met this guy named DJ Hollywood. And before 1976, MCs would just work the crowd; introduce people and stuff. “You’re rocking with the number one DJ, somebody say, ‘Oh yeah’” type of stuff. But DJ Hollywood was a rapper too, and he was actually the first rhythmic rapper I ever encountered. He was an incredible cat. He was the first rapper I ever saw. He’d do long, rhythmic verses and just moved the audience. They way people responded was unreal. So that’s when I started to look for a DJ, so I could get in front. Two years later, Grandmaster Flash became my DJ, and I started doing shows.

Talk about growing up in Harlem. How did its vicinity from Bronx affect you? What do you remember about that time, especially since you became famous pretty much out of your teens.

I remember I would travel up to the Bronx, which was just across the bridge. Fifteen minutes and we were right in the middle of it all. But hip-hop came to Harlem too. I didn’t always have to head to the Bronx to find it. I remember the vibe, the energy, and how nobody really fought because it was a movement of peace, for peace. Everyone was happy and vibing to the music. I remember seeing people hanging out their windows and jamming. People started to bring BBQ grills onto the street. You could hear the music, smell the food, and feel the energy.

So you’d run into figures like Kool Herc around the time too?

Of course, I met Herc early, back around 1975 when I was in the Bronx. I used to go to the Executive Playhouse, a club he used to perform at. I also used to go to his jams a lot too. And like I said, Grandmaster Flash actually used to be my DJ. We were good friends, and he was a really good guy. Later on, we became competitors and our friendship sadly went out the window.

How’d it happen?

He broke up with the Furious Five, and I became his MC for a while. And when Melle Mel came back, the rest of the crew came back too, so I left for my solo career. I ended up getting a record deal shortly after and asked Flash to be my DJ again, but he refused. I guess he wanted to stay with the Furious Five. So I went off, and that’s how we became more competitors than friends. I’m actually still friends with the Furious Five to this day though.

What about Lovebug Starski?

He and I had a love/hate relationship. We were good friends at first. We met at a club called Small’s Paradise, and I went over and introduced myself. He was a great DJ, but he could rap really well too. He was a versatile DJ, meaning he could play in any market and play all kinds of beats. He was very talented and was the first person I saw DJ and rap at the same time.

You mentioned Melle Mel too. What was that relationship like?

I actually met Mel in a street gang in the mid-’70s before either of us got into hip-hop. [laughs] As you know, there was a gang problem in New York at the time. Everyone was in a gang, and I met him in the Bronx. What happened was, one day in high school, I got jumped, so my big brothers and I joined a gang called the Peace Makers. It was simply for protection, to not get beat up ever again. We ended up running a Manhattan division of the Peace Makers where my brother was the leader, and I was the warlord. And Mel ended up becoming part of our gang, and we all became good friends.

In ’75, my brother went to jail, so I stopped gangbanging and took things easy. When I got back into hip-hop, I was DJing a lot at this time, and that’s when I met Mel again. By this time, he was already part of Flash’s crew. I think our whole timeline is incredible. There was a huge gang problem in ’75; everyone was in one. By ’76, there were way less due to hip-hop starting to take shape.

Speaking of early characters that were around, Russell Simmons was originally part of your crew, the Force. What was Russell like then?

We were the movers and shakers of our college, and Russell was the one who introduced me to the crew. Our leader, Bob Malone went by Obi-Wan Kenobi. [laughs] We were just taken by Star Wars, so we all took Star Wars names. [laughs] I was Kurtis “Sky” Walker! Believe it or not, Russell was C3PO. [laughs] Glen Black was Han Solo. As a matter of fact, my first DJing job was for Glen.

What did Russell do in the group? Was he always sort of business-minded?

Russell was a dancer! [laughs] But he always organized events and helped promote our gigs and stuff. He never rapped or anything; he was mainly a dancer. Basically, we were partygoers and excellent dancers. I won all the dance contests at the college. We were all popular guys in our own neighborhoods that met in college, and that was our relationship.

So you also knew his brother, Rev Run?

Of course, I taught Rev how to rap and how to DJ. This was around 1978. He used to practice in the attic, because their dad bought him a turntable for him to practice on. He was real young — five or seven years younger than Russell and I. He was running around going to park jams in Queens and stuff. And at the time, calling someone your “son” was a compliment, similar to calling someone your protégé. So “Son of Bambaataa” was Africa Islam, for example. And Run at one point was the “Son of Kurtis Blow”! [laughs] Right after I was signed, he was my DJ for a while too, actually. Rev Run was my disco son; we’d play music, and have big fun!

You mentioned your first contract. How’d that day feel? Did its importance strike you?

It felt great! I mean, no, I didn’t know the significance or historical value of it at the time, I was just happy to get out there. The real impactful situation was when “The Breaks” went gold. That was incredible getting that first plaque. It was the first certified gold rap song. Wow, it was great!

Was it a one record deal or did they actually want to invest in your career as a performer?

It was for two records, given only if the first record sold more then 30,000 copies. And if the second single sold more than 100,000 copies, I would get a chance to do a whole album. But I blew up hugely. The first joint sold more than 30,000; it sold 370, 000! The second was “The Breaks,” which sold like 900,000 or something — it was a ridiculous figure. So Mercury then signed me for a four-album deal. I was the first rapper to sign to a major label.

Talk about “Christmas Rap” and when it blew up. What went into it?

Writers from Billboard magazine came to Hotel Diplomat one night when I was performing with Flash and they wanted to do a record with me. We rocked it that night too. So they wanted to pay for the studio time, promotion, flights, all of that. So we went in and cut “Christmas Rap.” After that, they went and shopped that around to about twenty different labels.

To many, you were just the guy from the neighborhood. What was the local reaction like?

All my old buddies, even my old block, my hustler buddies, everyone was just so happy! That’s what hip-hop was about then. If you were involved and made it big, you were an icon of the community. Everyone knew you and supported you. You could walk around the block and just shake hands forever. You didn’t have to worry about people robbing you, because you were one of them. The lyrics now talk about how much you got, and I think it alienates you from your own people. Back then, rap tried to uplift with those gold chains, not separate with status symbols. Nah, everyone loved my success, and everyone loved rappers back then.

With all the curiosity surrounding hip-hop, everything moved quite quickly for you. Talk a bit about working on Krush Groove, and what about that experience stands out to you now?

What stands out is that it was a lot of work for me! [laughs] At that time, I had moved on to producing records too and was New York’s number one producer. I won awards for producing in 1983, ’84, and ’85. But I eventually got burnt out. While I was filming Krush Groove, I was also producing three albums.

What were the notable stuff you produced?

I did the Fat Boys’ albums, and I did the Krush Groove soundtrack. So I was running around from studio to studio, coproducing this and that, and had to be on the set at 6:00 AM everyday. It was a lot of hard work. Actually, that time was when I got hooked on drugs. I got burnt out, and after that I had to stop doing it.

By the ’89, you had been recording for ten years. How were you feeling about your career at that point? How did hip-hop at the time strike you?

I was burnt out by then and moved to Cali. You must understand, the first time I DJed was 1972. I was so done and ready to retire. I was just too burnt out. The music changed, the audience changed too. I stopped listening to radio completely by the time NWA came up. They were going hardcore, too hardcore. And being gangster wasn’t me. I already had made my accomplishments by then.

Your lyrics remained pretty much positive through your career, even as gangster rap became popular.

It was tempting going gangster because I was from Harlem. I was part of that hustling lifestyle; I was in gangs; I knew cats who perpetuated unspeakable violence. This was the life I lived before I became a rapper, so why talk about it when I was famous? There was always something in me, even back then, that made me want to have a sense of integrity in my music and just be on another level. My lyrics manifested being upbeat and uplifting.

But “8 Million Stories,” however, was a bit harder than your other work.

Yeah, it was harder. To me it was a gangster tale. But it was written from more of an outsider looking in. “8 Million Stories” is considered by some to be the first gangster rap song though. I ended up being the first to do so much. Now that I’m a minister, I can see that it might have been God inside of me the whole time, telling me to stay strong.

What are your thoughts on today’s hip-hop? I’m sure it’s something people ask you often.

I’ll keep it positive because I’m a spokesman for the older generation and do see frustration coming from my peers. But I think in general, rap flows these days are incredible. They’re faster, wittier, more complicated, and there’s so much variety. The lyrical content is another thing. [laughs]

Another great thing is that rap is so international right now. When I went to Europe, I had people tell me they learned and even practiced English because of old rap songs. You go to France, they rap in French. Germany, they rap in German. It’s incredible how people embraced hip-hop around the world who now rap in their native tongue. I think that’s the most incredible evolution.

And after all your travels and performances, you took time off and essentially retired. Then you became a licensed minister?

Yes sir, licensed and ordained, praise God. I’m at the church right now actually.

Currently, you tour with pioneers of your era and you’re involved in a documentary tentatively called The History of Rap. But with all your history, what do you want to be most remembered for?

As a man with integrity who was also a man of God and who loved helping people.