[Originally Published in Wax Poetics Issue #31 and Wax Poetics Japan Issue #2 Cover Story]

“It’s Slick-Rick-style,” Rick Rubin says, nodding to Jay-Z, smiling. “Yeah, I wanted to take it on some old-school, storytelling shit,” responds Jay.

The exchange, from the making of “99 Problems” (off the film Fade To Black) is a testament to MC Ricky D’s influence as a storyteller, a master of voices and characters, small details and nuance. His voice distinct and with presence, goofy yet sharp. Punch-ins, endless quotables, jokes — all these have been attributed to Rick by the most respected of MCs, spawns who came later who hold him as a venerated magician of words. Ghostface for example: “As far as number one of all time? For me it’s [Slick] Rick.”

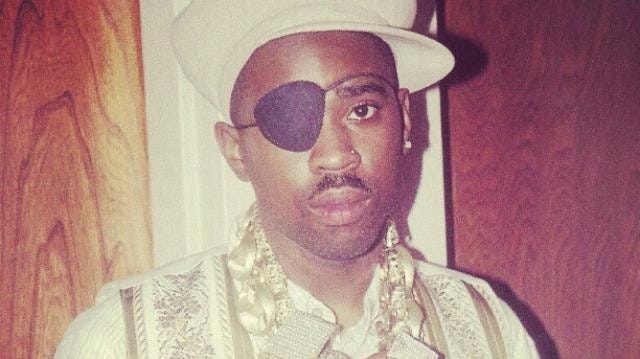

Decades since The Great Adventures Of Slick Rick went platinum, his colorful writing and delivery has been countlessly copied, covered, and referenced. MC Ricky D’s fluidity is a gut-punch that disarms its audience. His spirited fashion aesthetic— eye-patch, gaudy chains, literal crown — has to an extent also impacted the mainstream. You can now purchase Slick Rick costumes come Halloween time.

No longer in headlines for music or legal troubles, Rick’s vocal about the responsibility of his decades old craft. The gun trial and subsequent immigration hurdles now behind him, he says: “Rap can reach kids and can help adults reach kids. It should be utilized,” says the forty-three-year-old, about to perform to a crowd of mostly old heads and youngsters, many of which in both their own respective ways, grew up on his words. “These kids weren’t around when hip-hop started. So we, as the artists, can’t keep living in the past. Hip-hop is an adult now, so it should act like one. I want future generations to eventually benefit from our art.”

Rick (as of this writing) is making an album at his own pace and enjoys the quiet life he’s earned, touring in short spurts and making occasional guest features. Times change but like Jay and Rick Rubin pointed out, Slick Rick is omnipresent; a point of reference, a living generator of style who wrote some of the best rhymes generations now have the immense pleasure of hearing and laughing out loud to — just like we all have for decades.

What are your days like now?

I just take it easy, taking care of things and such.

Do you still get recognized often?

Yeah, I still get recognized. I mean, there aren’t too many people walking around with an eye-patch on, so it usually sparks their memory [laughs].

You came to the US when you were eleven-years-old; what were the immediate differences between England and America that you remember?

What I remember about London is [that] they didn’t play any black records. Records I grew up with were common stuff like The Beatles, Bill Haley and stuff like that. I love that stuff; don’t get me wrong. But when I came to the Bronx it was a lot more multi-cultural. The black soul of the ’70s was in full effect! Shaft, Bruce Lee, and all that was going on! America, the Bronx specifically, was exciting and a lot busier in comparison.

What sights did you see as hip-hop was becoming real popular?

When it first came out, it was the same story you’ve heard; people started break dancin’, people would bring out huge speakers for block parties, violence stopped for a while. It was a great sight to witness. And great groups started to formulate, like The Cold Crush Brothers. And all this happened in the Bronx!

People used to do routines, people started looking for records that had a reputation for being dope¾ it was great. Guys started freestyling over these popular records, and young artists were very conscious of peoples’ reaction to those records. They were very aware of the routines they were doing. And they were onto something ’cause those same records and routines are still popular today. I also remember cassettes and how important they were too. That really helped popularize hip-hop a lot.

What were you listening to at the time?

It was the disco era, you know? People were really diggin’ disco, and that’s what everyone was playing. A lot of people forget that disco was a huge part of hip-hop when it first started. Heartbeat by Curtis Mayfield was real popular. Gloria Gaynor, and those kinds of records were everywhere. You wouldn’t think I was a disco head, but I was listening to a lot of disco then. [laughs] I also liked Smokey Robinson and Gladys Knight too, of course. But everyone was getting down with disco whether they like to admit it [now] or not. [laughs]

Talk about The Kango Krew and how it developed your career.

It was a group of guys I went to high school with. We didn’t have any instruments or headphones or anything. [laughs] We would just bang on the desk and rap along to it. We would come up with real slick routines and people in school loved us. We would also do songs that were popular at the time, so we got a lot of recognition. We named ourselves The Kango Krew because we loved the Kangol hats, and just that whole style; Puma, Adidas, British Walkers, Clark Walabees, Cazals¾ everything that was hip and stylish at the time. We’d wear suit jackets and perform around the school and neighborhood. We were nuisances really [laughs]. And once we graduated, two of us went onto make records. That’s primarily the reason why people even know of the Kango Krew, because Dana Dane and I went on to become famous.

How is your relationship with Dana Dane?

Our relationship is good. I was glad to see him do well for himself after we grew up. I mean, he made his mark on hip-hop with “Nightmares” and “Cinderfella Dana Dane”. I think his first album did real well too, and I was glad to see it. I know its been reported that we feuded or whatever, but that didn’t happen. I wish him well.

Do any tapes of the Kango Krew tapes exist?

Naw. [laughs] We were poor kids. We were just banging on tables and having fun.

You were one of the first to wear huge, over-emphasized jewelry. What made you do that originally?

To the mainstream public, that wasn’t seen too often until rappers like me did it. But from the areas we grew up in, you’d see that all the time. Dudes would be wearin’ huge ridiculous gold chains! [laughs] They probably didn’t get the chains in a nice or legal fashion, but they were considered the kings of the neighborhood. So we took from these older cats and used it for ourselves when we got famous. We were just trying to be like the older brothers. Plus, once women were exposed to such giants in their own community, why would they care for the small fries of the world? [laughs]

That’s how it started, and it just got bigger and bigger; I definitely didn’t invent it or anything. Nowadays, some rappers look like they raided Queen Elizabeth’s hidden chest. [laughs] It’s ridiculous.

Take us back to the day you met Doug E. Fresh.

Well, I’ll always remember because he was the original human beatbox, which was a fairly new branch of hip-hop then. I was introduced to him twice; once at a skating rink that he was performing at, and the other when he was judging a rap competition. He was already known and was judging different rap competitions around the city. At the skating rink, the first time we met, I was bugging him like, ‘I’m a good rapper [imitates kid’s voice], you should hear me, you should hear me!’. But he didn’t pay me much attention ’cause I’m sure a lot of people bothered him and stuff.

So the next time I saw him was during a battle my friend was in. My friend asked me to go on stage and rap with him. It was a very big contest, and we went up against some very good neighborhood rappers from the Bronx. Anyways, we came it second [whispers: “although some people said we came in first”]. That’s when Doug recognized me and said what’s up. That’s when I told him we had met before and I was like, “I told you I was good, you should put me on”. [laughs]

Do you remember any of the original routines you did back then?

We’d do “La Di Da Di” all the time. He’d beatboxed over the “Impeach The President” break a lot too. Meanwhile, I ‘d do my story raps. A lot of people weren’t into the story side of rap then, so I guess I just sorta fell into it. I’d just try to tell stories people could follow along to.

Did people notice immediately?

Yes. People seemed to like my shit right away.

Where did the phrase “La Di Da Di” come from?

I guess it comes from my upbringing in England. A lot of my phrases came from my childhood and stuff I picked up from other people’s music. Like The Beatles for example [Sings The Beatles’ “Michelle My Bell…”]. You don’t even need to say these artists’ names, you just have to touch on their music and people will get it. So I guess I incorporated influences from America and England into my songs.

You made a lot of beats when you were younger. Did you stop producing for a reason? Rapping just more your calling?

When I was making my first album, making beats came easy to me. There wasn’t complicated equipment or stuff like that. Things were just basic. So when hip-hop became bigger, they came with all this complicated machinery and the sound sounded more clean and professional. So it became hard to compete with professional producers. And plus, record labels would try to push producers onto your projects, so it was difficult to grow as a beatmaker if you weren’t already one. I guess it’s wiser from a business standpoint. But hey, the beats on “Children’s Story” and “Hey Young World” and “Mona Lisa” weren’t so bad right? [laughs] I made all those beats, and I liked what I did on those songs.

What sticks out in your mind about the time when you were making Great Adventures… ?

It was a time of breakthroughs. I mean, I was a mail clerk making five-hundred-and-sixty-bucks a month. I had a girl and the whole shebang, so I had to be budgeting shit all the time. But I was basically still doing okay for myself. While you’re just making ends meet, you don’t realize how hard you struggle ’cause you just wanna work and have your own place. And from bugging Doug E. [Fresh] all the time, he gave me three-hundred-dollars for a show.

I know it may sound petty now, but you could imagine going from a five-hundred-dollar budget, paying three-fifty for rent, plus you gotta buy food and tokens to get to work? It was hard. Then all of a sudden, I was making three-hundred-bucks a night! In two nights, I could make what I made in a month! The difference in money was a big jump. Getting paid to do a hobby, something that’s fun and exciting, and you’re getting paid for it? It blew my mind. That’s what I remember bout that era.

In Brian Coleman’s Check The Technique: Liner Notes For Hip-Hop Junkies, you said you didn’t like The Bomb Squad’s work on Great Adventures. What about it did you specifically not care for?

Certain beats and me don’t work. “Teacher, Teacher” was garbage. No disrespect, but it was filler to me. I mean, you got people [working] on a record behind the scenes who have to keep score of what they think the public would like, and that’s when they brought in The Bomb Squad. You have A, B, and C level beats. Of course you have your D and F level beats too [laughs], but you always want to stay in the A or B levels. I mean, sometimes a good beat just doesn’t bring out the best in an emcee, or vice-versa. And that was the case with Bomb Squad’s beats for me. I mean, I like their beats, I just didn’t think they work well with my style.

Did you ever work directly with Eric Sadler and Hank Shocklee? How were those sessions?

Actually, we only worked directly with each other once. It was for “Lick The Balls”. They were great guys, and it was fun as far as I can remember. I knew that they had done songs for Public Enemy and were well respected, so I was excited. They’re nice guys and working with them was actually cool. Just ’cause I didn’t like some of their beats doesn’t mean I don’t respect them. “Lick The Balls” is definitely my favorite of all the tracks they gave me.

“Children’s Story” has been covered many times. Have you heard these other versions? What do you think of them?

It just proves to me that the public has an excellent perception of things¾ and not the experts. Time and time again, it proves that experts don’t know as much as they think they do. “Children’s Story” has been covered so many times, and it just means that I connected with the public.

How was your relationship with Russell Simmons and what role do you think he played in your career?

Well, he was a record exec type, manager, whatever you wanna call it. But being an exec means I didn’t see him as much as I would’ve liked. As the artist, you want to work closely with the guy that’s gonna make the final decisions on your record. We had our ups and downs. Pretty much what I told Russell was that it was hard for me; going from a kid who had two rap songs, and having to make twelve songs overnight was difficult. Plus he had all these “experts” telling him what was best. I felt he didn’t know what was best for me as an artist; he was all business. Don’t get me wrong, I wanted to make money too. But he didn’t take a lot of my suggestions on those early records.

Can you give us an example of how you guys disagreed?

I wanted “Children’s Story” and “Mona Lisa” to be released as singles first, but they put out “Teenage Love” instead. I mean, it’s not a bad song, but in a fast era where hip-hop was booming, you want to put your best foot forward, I felt. And you have cats like Rakim and Kane out there too, and they’re killing it, so it didn’t make sense to me to put out a slow-sounding record. It’s almost like you’re defeating your own purpose. I mean, “Teenage Love” was a cute song and all that, but still. Luckily for us, the people didn’t abandon ship. Russell and I had a lot of minor conflicts like that.

Big Daddy Kane and Rakim were your contemporaries at the time. What about them struck you?

They took hip-hop to the next level. They were skillful in many things, and they obviously perfected the art of battle rapping. Their beats were gritty too! You know how they say, ‘if you can make it in New York you can make it anywhere?’ Well Kane and Rakim got love from everyone in New York. They brought everyone’s skill level up by being so skillful themselves. Their grit was great.

Discuss the next album you made, The Ruler’s Back. What do you think of it when you hear it now?

I don’t like it. It was during the trail, after I was incarcerated for the whole gun possession thing, so I wasn’t able to do my best. A lot of the music was added to my vocals after the fact, so I don’t think it complimented me correctly. It definitely wasn’t my best work. The rhymes were too fast, so you couldn’t get into the stories. It was just really rushed. I think my best albums are the first and the last album.

What about Behind Bars then? You made that after getting out of jail. What was the process of making that like?

I recorded Behind Bars while I was out on bail and it wasn’t a good experience either. I only had such a little bit of time to do it in. Basically, I recorded The Ruler’s Back and Behind Bars in a span of two to four weeks. Behind Bars was rushed, and wasn’t what it needed to be. I needed outsiders looking [in] to slow everything down and not keep pushing these projects. But with those projects, nobody did.

So you consider Art Of Storytelling to be one of your best works. What was life like by this time?

Things were a lot more relaxed. I learned from the mistakes of the last two projects. People actually listened to the input I put into it. You could pretty much hear the variety of stories I told on that one. I was also able to collaborate with the hottest artists of that moment; Outkast, Snoop, Nas, and Raekwon. A lot of those cats I worked with showed me a lot of respect too. That was a good experience and I think the album reflects that. To me, this album was an achievement. I went from making silly rap songs in ’85, to being incarcerated, to being back out, struggling, then making a great album. It went gold, so I’m proud of it. So now, I get to say [yells in a loud, boisterous voice], ‘My last album went gold!’

Are rumors about an upcoming album entitled The Adventure Continues true?

Yeah, but I’m only releasing it when I’m ready. We’re recording it at the house and we’re taking our time with it. No record execs this time! [laughs] It’s a constant work in progress.

How’s occasionally traveling and performing with a live band?

It’s real fun. I get exposed to a broader audience and younger fans, and they show me respect. As far as the live band thing; it’s different and real refreshing in a way to play with solid musicians backing you.

Do people ask you about your eye-patch? There have been many stories about it. What’s the real story?

Well, I can’t see out of my right eye. A window shattered when I was about two-years-old and glass got into it. And the patch is for cosmetic reasons too. It’s like Superman going into his closet before he has to face the world. Instead of a Superman suit, I throw on my eye-patch before I rap. [laughs]

As a very revered rapper, where do you see the art of rapping going in the future?

I think people will just try to perfect the personality they want people to hear. Some of us just kick raps¾ and some are very conscious of how they portray themselves on wax. Nowadays, people don’t care much for stories, they just wanna hear their favorite rappers’ personality shine through. It’s gonna be less person and more persona, you know? So I think that’s where lyricism is going, not necessarily good or bad, just changing.

How do you see hip-hop advancing?

I see it as a racial melting pot, which is a wonderful thing. I mean, hip-hop is already multi-racial and diverse, but it’ll continue to be more widespread. It’ll be like a pulpit for the world¾ like in church. You get the right people in front of a pulpit and you can change the world.

I interviewed Chuck D recently and he said something to the affect of: “People nowadays use hip-hop as a toy, instead of a tool”. Would you agree with that?

Definitely agree. Rap is being disregarded as the art it can be. Hip-hop should be used to help people, to reach kids, to get messages across. Like all art, it can teach.

Do you hear yourself and your influence in contemporary rappers?

Sure I do. But I’m sure you could hear Cold Crush Brothers in my style too. I think it’s only natural. It’s all about making our art, hip-hop, richer. If a child is hungry, you feed it porridge. If humans out in the world are actually hungry for smart, digestible hip-hop, than its our duty provide it. Each one, teach one.

What has been your approach to writing stories you’ve told?

Well, I think it comes from high school English class; believe it or not. [laughs] That’s where I learned to strategize and layout an essay. First you have your intro, then your body, then the conclusion. And hip-hop is pretty much just like that — you have your three, sixteen bars, and a little chorus. And your three bodies have to relate to the chorus. And all the while, you display your level of maturity and smarts through what you say. You have to make things sensible and accessible. Otherwise, it’s like force-feeding somebody liver, and nobody likes liver. [laughs]

What other songwriters have been influential to you?

I love The Beatles. I like The Supremes and Dionne Warwick. Oh, and Queen too. [sings beginning of Bohemian Rhapsody: “Mama, just killed a man…”]

How do you want your songs to be remembered?

I just want people to enjoy my records. When you go to a club and you’re getting your drink on, you want to do so while [you’re] listening to good music. If the music sucks than you’re just gonna feel like an alcoholic. [laughs] I don’t want to make anyone feel like an alcoholic.

What do you want younger cats to gain from your recordings?

Just to know that my raps have morals in ’em. You don’t always have to be tough, acting hard and all that. Sometimes rap celebrates the worst qualities of our neighborhood, and I think my music has lessons hidden within the songs. Like, I’d use humor to get a message across, and kids should use other ways of asserting themselves without violence and all that.

How would you want your legacy to be worded?

That I’ve just always been honest and tried to write humorous stories that anyone can enjoy.

David Ma is a frequent contributor to Wax Poetics and would like to thank Connie Price for his assistance in reaching Richard Walters.